Ice Was Nice

When I first moved to Southern California, I was amazed at the size of some of the houses and the yards, but what really blew me away were the driveways. The what? Yep, the driveways.

When you’re a California native, a driveway is, well, a driveway. When you’re from the Midwest, a driveway is something that needs to be shoveled every time it snows. A quarter-mile long uphill driveway? A major league payday.

That’s why the winter of 1961 was so weird. I was 10 years-old, the month was January, and the weather was cold enough to make the tips of your ears tingle, and for my buddy Mike Geier to do his famous I’m-going-to-drench-my-head-in-water-go-outside-and-watch-follicles-turn-into-popsicles icicle head imitation.

But even though we could break off chunks of Mike’s hair on a daily basis, we were still awaiting our first snowfall. There were lots of clouds, lots of wind, lots of cold but no white stuff.

My spending money came with the first snowfall. Without it, I was a landscaper without lawns, a window washer without windows, Matthew McConaughey with his shirt on. I needed and loved the snow, but the Big Guy in the sky wasn’t cooperating. I knew that cold weather was the necessary evil that went along with snow. And snow? Merely the greatest toy ever invented.

When I got older, snow, ice, and cold quickly lost their appeal. Adults have to drive to work on slippery pavement, dig out of snowplow-induced ten-foot drifts, and watch the street salt and slush do a frenzied termite imitation to the side of the Buick. And, of course, adults have to wear whose fancy go-to-work clothes that never ever keep you warm. Kids don’t have those problems.

All they have to do is put on 12 layers of clothes—none of it matching—and go frolic in the snow. They don’t have a best-dressed award. Instead, there’s the best snowball arm—the longest distance thrown and the most resourceful in a full-on snowball attack. That’s important. The biggest bummer? Getting all your snowball battle gear on and then realizing you have to completely un-gear and go to the bathroom.

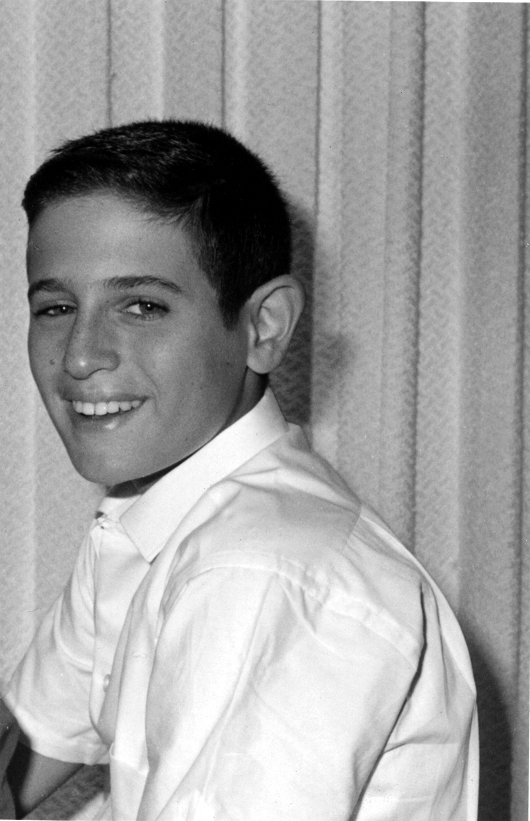

Don’t let the smile fool you….all gloves are off in a snowball fight.

In our Midwestern version of a 1960s street gang, every neighborhood had its own snow fort. We would gladly sacrifice our little brother, little sister—or both—to defend it. During school hours, there was an unwritten law that no one messed with anyone else’s fort. As soon as that final bell rang though, everything—and every fort—was fair game.

A good snow fort could be six feet tall, ten feet long and eight feet wide. We’d cut peep-and-throw holes in the side of each fort and spend every waking hour making snowballs, fixing up cracks in the large snowball foundation (you could only do repairs on days when the snow was good packing), and loading up for the next battle. The game itself—the heart pounding in your chest during the chase, the redness in your cheeks after an enemy “face wash”—was all that mattered. Winning was sort of an unnecessary byproduct.

But this was 1961, our snowless winter. Every evening we looked skyward, hoping for snow-filled clouds. One evening, I remember things looked especially promising: full-on cloud cover. I went to bed that night excited, hoping that when I woke up everything would be blanketed in white.

As I tried to sleep, I heard a sound that was vaguely familiar but didn’t seem appropriate. If this was March through October, rain would make sense. But it wasn’t… and it didn’t.

The next morning, I woke up to a picture postcard. It had rained all night, and then the water froze. The entire neighborhood looked like a glazed donut. Perfectly formed icicles hung from the trees and the roof. The sun reflected off the ice that covered my driveway and the streets. I had never seen anything like it.

After taking two steps from my house, I slid all the way down the driveway on my chin. As I lay there face down, I wondered if I could skate on this stuff. I ran in, laced up my hockey skates, grabbed my stick, slapped some electrical tape on it and hit the street.

Before I knew it, Mike Geier and I, along with all the boys from the ‘hood,’ were out there playing hockey in the street… on skates! It was a miracle. Our street had never, ever frozen solid before.

After a full eight hours of skating and laughing and scoring and face plants and bouncing pucks off the side of Mr. Estrin’s Ford Galaxy 500, we all collapsed exhausted on the curb. As we sat with our elbows on our knees, wordlessly watching our breath come and go in the expanding shadow of the sun, it began to snow.

The snow was what we had been waiting so long for, but no one was jumping up and down. We all knew that playing hockey in the streets had been really special. We were replaying in our minds what would turn out to be a singular adventure in our lives.

Who woulda thunk it? Winter was just about to break down and finally give us snow—but we didn’t care.

For the time being, ice was nice.

Ice Was Nice can be found in my book: Never a Bad Day