From 30 Years of the Ironman World Championship, by Bob Babbitt

The room is hospital white, the floor polished squares of institutional linoleum. Sterile. Unforgiving. The smell of despair hangs in the air like a soggy cloth coat on a withered old man. This is no place for a little girl. Barely five years old, she lies on her back, surrounded on all sides by large men and women wearing rubber gloves and thin blue masks.

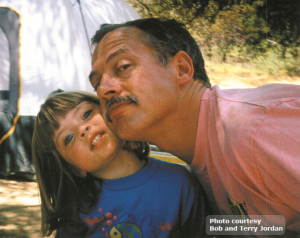

FBI agent Bob Jordan strapped his frail little girl with the peach fuzz-covered head into the Baby Jogger for another training run around the neighborhood. They were a team. Team Jordan. Bob, Emily, and Terry, who rode along-side on her bike or in-line skated until it was her turn to push Emily in her jogger. Bob and Terry met at the Bay State Triathlon in 1988, and their relationship has been multi-sport-based ever since. Bob was racing that day and Terry was cheerleading. It was the start of something pretty wonderful.  “We always worked out together,” remembers Terry. “When I was pregnant with Emily, I rode beside Bob on his long runs. We sorted out most of our major issues during those workouts. After Emily was born, we took turns pushing the Baby Jogger around Lake Miramar.” A short pause, “Then Emily started to talk… ” And she never stopped. So Terry stayed home while Bob and his little girl went out together for long talks and long runs. After he tucked her into the Baby Jogger, Bob would look Emily in the eyes and smile. “Who’s the lronman, Emily?” She never hesitated, especially when he tickled her. “Daddy’s the Ironman!” giggled Emily. “Daddy’s the Ironman!” “What’s an Ironman do, honey?” “He swims, bikes and runs and runs, bikes and swims, Daddy!” They’d both laugh and daddy would go about his business, putting in the miles with his little girl giggling the whole way. “The two of them were great training buddies,” says Terry. “They almost wore that Baby Jogger out.”

“We always worked out together,” remembers Terry. “When I was pregnant with Emily, I rode beside Bob on his long runs. We sorted out most of our major issues during those workouts. After Emily was born, we took turns pushing the Baby Jogger around Lake Miramar.” A short pause, “Then Emily started to talk… ” And she never stopped. So Terry stayed home while Bob and his little girl went out together for long talks and long runs. After he tucked her into the Baby Jogger, Bob would look Emily in the eyes and smile. “Who’s the lronman, Emily?” She never hesitated, especially when he tickled her. “Daddy’s the Ironman!” giggled Emily. “Daddy’s the Ironman!” “What’s an Ironman do, honey?” “He swims, bikes and runs and runs, bikes and swims, Daddy!” They’d both laugh and daddy would go about his business, putting in the miles with his little girl giggling the whole way. “The two of them were great training buddies,” says Terry. “They almost wore that Baby Jogger out.”

Among the crowd of blue masks, there were two eyes that the little girl recognized – the ones that were welling up with tears. Her mom grasped her hand and started to tell her a story about Sally the caterpillar.

In February of 1996, at the age of four, Emily was diagnosed with leukemia. That spring and summer, Bob and Emily trained together for the Vineman Triathlon, a full Ironman-distance event in the wine country of California. Bob had always wanted to be an Ironman, and had sent in his application for 10 straight years. For 10 straight years, he called the lronman office on May 1 and received the same “better luck next year” news. “Every year since 1985, I’d do this same pathetic lemming-like deal,” recalls Bob. “I’d send my money in for the lottery, make my call and get my ‘no.’”

That August, Terry gave birth to an 11-pound, 4 ounce baby boy who lived for all of two minutes. “You’d think that a big baby means a healthy baby,” says Bob softly. “We learned that’s not always the case.” The child’s name was Thomas and, to this day, the doctors couldn’t tell you what went wrong.

Emily’s leukemia progressed so quickly that Bob and Terry were forced to leave San Diego and move with Emily into the UCLA Medical Center. She was being prepared for a bone marrow transplant, the last of her dwindling chances for life. She was in the high-risk category, which meant that a donor had to be found… and soon. “There was no donor available,” says Bob, “and we knew that 20 percent of the kids die from the process of conditioning them for the bone marrow transplant. They have to bring the patient down to base level zero and then introduce the new bone marrow.” “I look back now and wonder, why did we put her through all that?” says Terry. “It’s an incredible process. No one allowed to visit… the isolation…But Emily was such a brave little person.”

Terry was pregnant again, and the best chance of success for matching bone marrow was through a sibling. There are six points that doctors look to match when considering a donor. A match on four of the six is considered good. Emily’s chances of survival without the transplant were now single digit.

Little Timothy was born early, but wasn’t a match on any point.

“Sally the little caterpillar ate so much her belly became very big and began to hurt,” Terry told Emily, “It was so big she couldn’t breathe. The little caterpillar tried rubbing her belly with one of her many, many feet but even that didn’t help to make the pain go away.”

“At that point, we thought there was very little hope,” says Bob. “Then they found a mother on the East Coast who had lost her baby, but had saved the umbilical cord.” The cord matched on five of the six points. “We thought maybe this was our lost baby coming back to save Emily,” remembers Bob. On March 3, 1997, Emily received her transplant. “When new bone marrow is injected, your body recognizes that something strange is being put into your system and fights itself,” says Bob. “It’s full-on war…the host against the graft”

A war that raged inside their little girl.

“Her spirit and will through all of this never ceased to amaze me,” says Bob.

On April 24, Bob Jordan left Emily’s room and walked into a wall of light. It was his 46th birthday, and he was surprised by a bunch of strangers and fellow FBI employees congregated in a hospital meeting room.

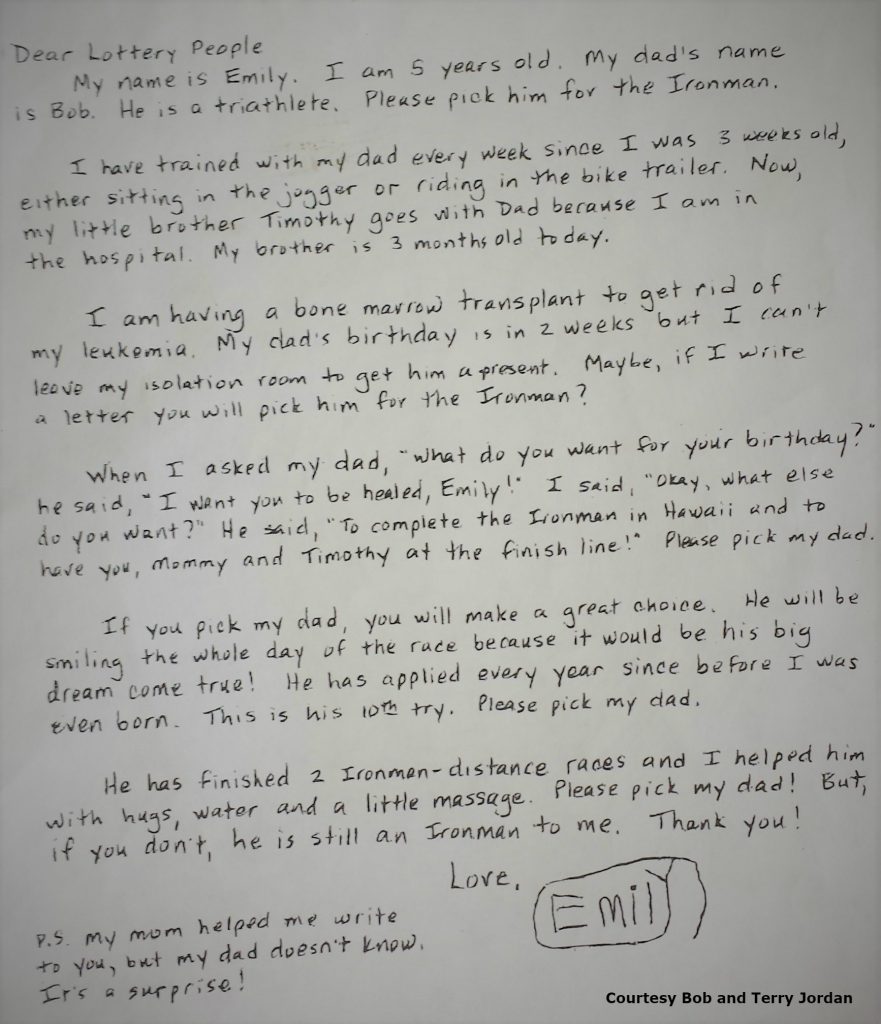

“They hand me this letter and tell me it’s from Emily,” says Bob softly. “I figured it was a birthday card. You’ve got to understand. My little girl had been so sick. Whatever Emily had to say was very important to me.”

He laughs. “I guess Ed Muskie and I are the only two men to cry on national TV.”

The letter was indeed from Emily — with a little help from mom. It was addressed to the Ironman office in Florida and explained how Emily would like to see her dad get into the Ironman. She could be there with him. Strapped in the Baby Jogger, they could go on their long runs together again. After barely making it through the letter, Bob Jordan was handed a plaque from the Ironman office. He had been accepted into the race. “I could have fallen over,” says Bob.

The men and women with the blue masks stood mesmerized as Terry told the story of Sally the little caterpillar. There was no movement in the operating room. The doctors and nurses, poised with their tubes and machines, were suddenly children, transfixed by the story. “One day, Sally decided that if she went to sleep, maybe her big belly and the pain would go away,” soothed Terry. “So she wrapped herself up in her favorite yellow blanket and drifted off to sleep…”

Emily was having a tough go, vomiting and diarrhea day and night. All her food came through an IV. She had open sores inside her mouth and on her bottom. When she went to the bathroom, parts of her stomach lining ended up in the bowl.

“The drugs attack the fastest-growing cells,” explains Bob. “Like your hair and your stomach lining.”

The little girl was having trouble breathing and her belly was swollen to twice its normal size. The doctors worried that she would asphyxiate.

Even when things were the worst, there was always a silver lining.

“I found something every day to be grateful for,” Terry says. “The support of our friends and family. The hard work of all the doctors and nurses. It was important to me to maintain that sense of gratitude”

”We had to make a decision,” says Bob. “The doctors felt Emily needed to have a machine breathing for her, and to do that she had to be knocked out because she would fight the machine.”

There was one more consideration: If Emily was knocked out, there was a 75 percent chance she would never regain consciousness.

It was a Friday night. Emily slowly put her feet to the floor and moved away from the bed that had become her full-time home.

“Where are you going, Emily?” Bob asked softly. His beautiful little girl with the big blue eyes didn’t say a word. She couldn’t breathe well, couldn’t speak.

“Anything we can do for you, honey?”

Emily just came over to Bob and crawled up onto his lap so he could hold her.

“You learn to change your priorities from ‘my child hit a triple’ or ‘my child was student of the month’ to ‘my child opened her eyes,’ and ‘my child squeezed my hand,” says Bob. “I remember looking at her and thinking, ‘I’ve been trying to get into the lronman for 10 years and you, someone who can’t even talk, pulled this thing off,'”

The doctors and nurses were still immersed in the story, which Terry was making up as she went along. “Sally the caterpillar woke up after many, many days asleep. She opened her eyes and realized her big belly was finally gone. She looked around for her yellow blanket, but that was gone, too! Instead, the yellow blanket had changed into wings and Sally the little caterpillar was now a beautiful butterfly.” Terry realized while she was telling the story that her little girl might not wake up from the procedure, that this might be the last time they would be together.

“The story was to let her know that when she woke up, she would be better. To me, this was a good story, no matter if she woke up or not,” says Terry.

That night, Emily went into a coma. She never woke up.

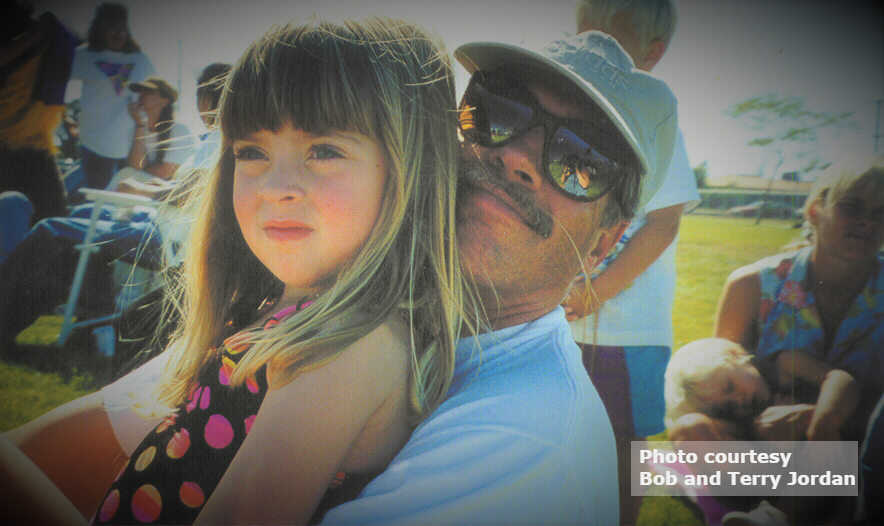

“There is nothing worse than losing a child,” says Terry. “But we’re still grateful for many things. Emily was a blessing, and we had her for five-and-a-half years. Timothy was basically raised in Emily’s hospital bed, so we have photos of Timothy with his big sister. The doctors were against it, but we told them, ‘No Timothy, no transplant.” Emily was proud of us for that. She told anyone who would listen that her daddy said ‘No Timothy, no transplant.’ The highlight of her day was when Timothy showed up.”

It is 8 a.m. on a Saturday a few months later. They are once again out at Lake Miramar, Bob stretching a little and tightening up his running shoes. Terry on her bike. Timothy squirming in the Baby Jogger.

Life goes on … and there’s an Ironman to train for.

“Emily wouldn’t want us to retreat from life,” insists Terry. The threesome head out for their workout, the lake shimmering in the early morning sunlight.

Emily never leaves their thoughts.

”There is an eternal nature to our children,” says Terry. “There was much more to Emily than her body.”

Terry pauses, “Emily is closer to us now than our own breath.”

Bob had an appointment with the lava fields of the Kona coast back in October 1997, and he wasn’t swimming, biking, or running alone.

“I know Emily was there with me every step of the way,” says Bob.

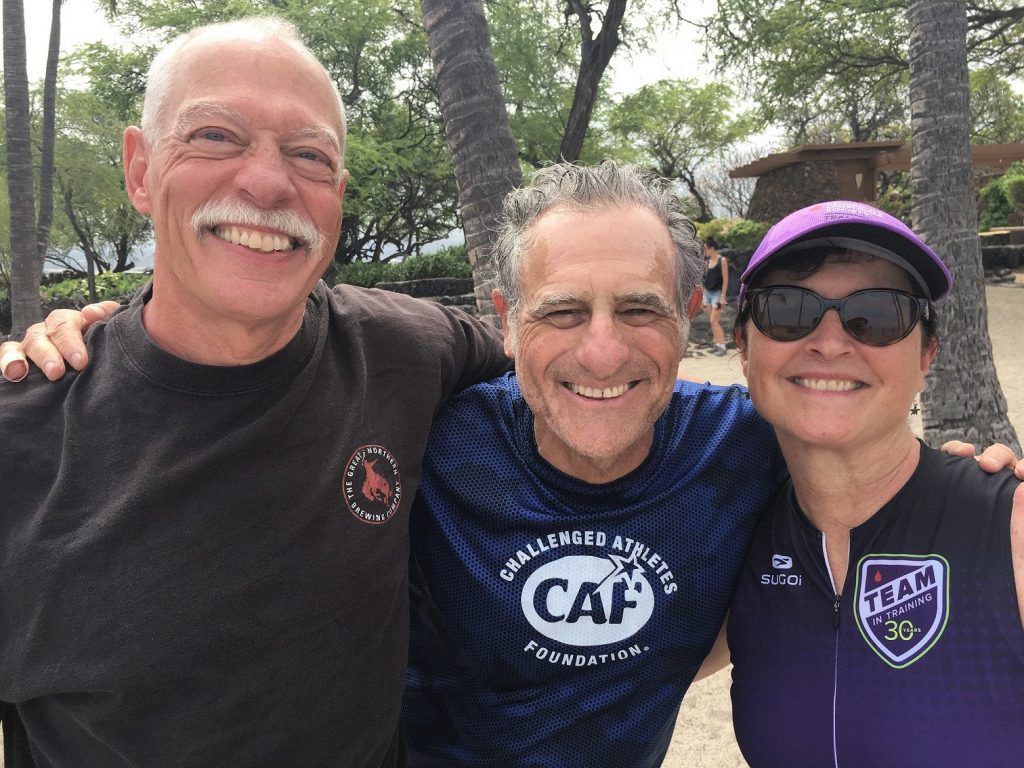

Postscript: After all those years of trying, Bob finally qualified to race the Ironman World Championship as an age grouper at Ironman Maryland in 2017. This October, as we celebrate Ironman’s 40 Years of Dreams, Bob – and Emily – will be swimming, biking, and running on the Kona coast once again.

Ran into Bob and Terry Jordan this past March at the Lavaman Triathlon on the Big Island.

Beautiful story. Thanks for sharing.