For our 2016 Kona Countdown, I’m counting down my 50 Favorite Ironman Hawaii Moments

Here are the top 25 moments…..

25

24

24

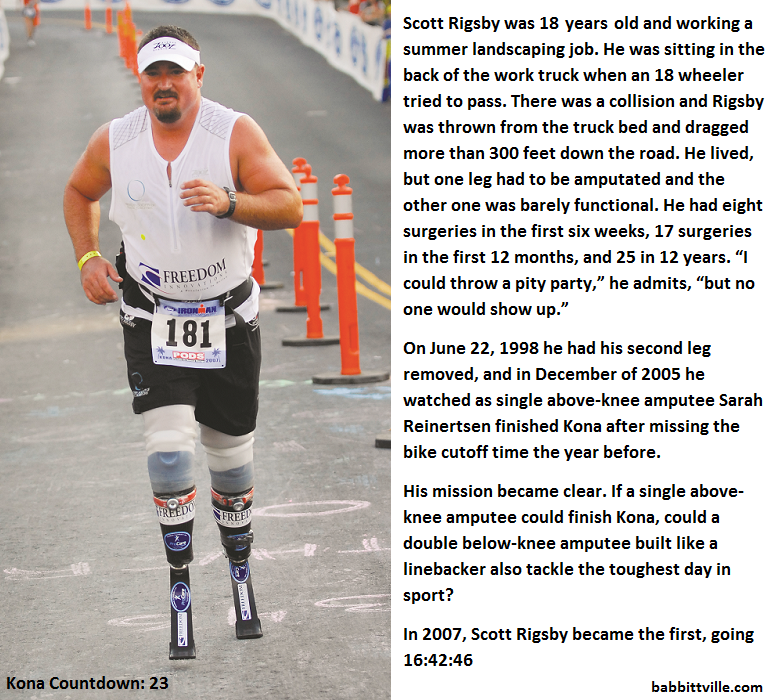

23

22

When Chris McCormack came to Kona for the first time in 2002 he thought he’d win the race. Check that. In a pre-race interview he said his goal was to win the race SIX times.

The chorus jumped him on that one. “Hey Chris,” they said in unison. “Before talking about six, maybe first try to win it once.”

McCormack found out the hard way that Madame Pele isn’t very fond of athletes who talk trash on the Big Island of Hawaii.

In 2002 he dropped out, in 2003 he walked the marathon, and in 2004 he dropped out again. In 2005 he finished sixth, he was second in 2006 by 71 seconds and then, in 2007, on his sixth try, he finally won the biggest prize in the sport.

After dropping out in 2008 and taking fourth in 2009, people thought he just might be done. The thought was that he was traveling the world cashing in on his one Kona win and wasn’t very motivated to put in the hard yards necessary to win title number two.

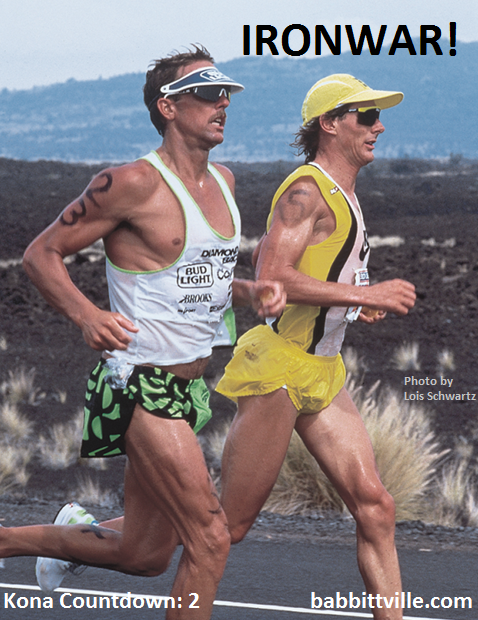

In 2010, at the age of 37, he arrived in Kona lean and hungry for the first time since 2007. He pushed the pace on the bike to get away from two-time champion Craig Alexander and took the lead in the marathon. But then Germany’s Andreas Raelert ran through the field and caught McCormack at about mile 22. They ran side-by-side for three miles, shared sponges and did their best to re-create the classic Mark Allen vs. Dave Scott battle at the 1989 Ironman.

“It’s like Iron War,” said Macca to Raelert as they shook hands and moved ever closer to town.

Allen got away from Scott on the last uphill on the Queen K Highway back in 1989.

Macca and Raelert crested that climb together, took a right on Palani, and started down the hill.

Macca, who was fighting cramps, dug deep and, when Raelert slowed down to grab fluid at an aid station, he surged away from Raelert.

Andreas Raelert looked to be the fresher runner as they ran side-by-side, but the reality was that he had burned way too many matches closing the gap to Macca and had absolutely nothing left.

After over eight hours of racing, the gap at the end was only 1:40, 8:10:37 to 8:12:17.

Macca had proven the doubters wrong.

While winning once was great….

winning twice was even better.

21

Other than that, everything went swimmingly.

Now qualified for Badwater, although he hated every single step he ran in training and on race day, he dropped to 177 pounds and finished fifth in his first Badwater.

He took a similar approach to triathlon. His first one? The three day, 320-mile Ultraman on the Big Island of Hawaii. Of course, he ended up borrowing a bike since he didn’t own one.

He took second.

So why should it be a surprise that the guy who would go on to set a world record in 2013 with 4,025 pull ups in 17 hours would start the 2008 Ironman only after he and a buddy parachuted into Kailua Bay? They were then taken to shore, got into their swim gear, and started the Ironman with everyone else.

“So David,” I asked him after he finished in 11:24, “now that you’re an Ironman will you be shaving your legs like everyone else?”

“No sir,” he responded quickly. “David Goggins will never be shaving his legs.”

Nope. Instead of shaving his legs, David Goggins simply continued on his quest to raise money for Navy SEAL families and to travel the globe looking for unique ways to suffer.

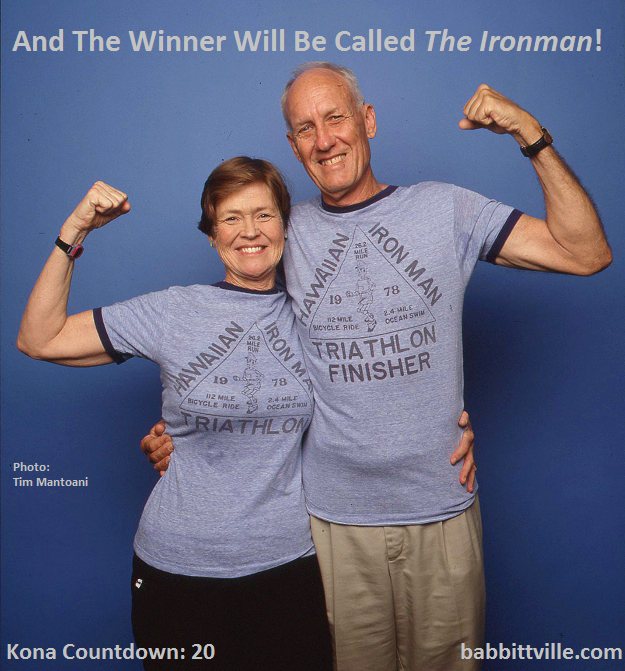

20

At the awards ceremony for a running event called the Perimeter Relay on the island of Oahu, there was a discussion as to who was the world’s fittest endurance athlete after an article proclaimed that it was Tour de France legend Eddy Merckx. Some in the crowd thought the runner was the fittest while others thought it might be the swimmer and still others believed it was the cyclist. Commander John Collins, who had raced some of the early triathlons around Mission Bay in San Diego, got up in front of the group and said that he would put on a race combining the 2.4 mile Waikiki Rough Water Swim, the 112 mile Around Oahu Bike Ride and the 26.2 mile Honolulu Marathon. The winner, he said, will be called The Ironman. In February of 1978, 15 adventurers stepped to the line to give this new event that was put on by John and his wife Judy a try. The first-ever Ironman Champion was taxi driver Gordon Haller and he went 11:48:40.

19

People sometimes don’t think of all the ramifications of PED use. Not so much on the athlete who cheats, but on everyone else. Back in 2004, Germany’s Nina Kraft won the Ironman with four-time Ironman World Champion Natascha Badmann an unbelievable 17 minutes back in second place.

Kraft’s behavior was strange that week. At the pre-race press conference, she was bundled up like a mummy and shivering. Did she have the flu? Maybe the third place finisher from 2003 won’t be a factor this year, I thought.

When she crossed the line that day with her huge win, there seemed to be no joy surrounding her victory. Her head was down and she never smiled.

Later we found out why. Nina Kraft became the only person in Ironman World Championship history to win the race, test positive for drugs, and have her title taken away. She admitted that she felt so much pressure to win that she resorted to EPO.

Besides leaving a black mark on the sport and ruining her own career, how about poor Natascha Badmann of Switzerland who, despite now being a five-time champion, certainly didn’t feel like one. She didn’t get to break the tape or wear the traditional wreath or speak at the awards ceremony.

To me that was oh so wrong.

So what did we do? The Ironman sent her trophy to me in San Diego along with a winner’s wreath and the finishing tape and, on stage at our Competitor Magazine Endurance Sports Awards in February of 2005, with 500 attendees giving Natascha a well-deserved standing ovation, we recreated the Ironman finish on stage so that the woman whose smile and infectious joy always lit up an entire island, could finally have her very special moment in the sun.

Natascha Badmann is now a six-time champion and this October will be her final pro race in Kona.

I will remember all of her wins, but her fifth one most of all.

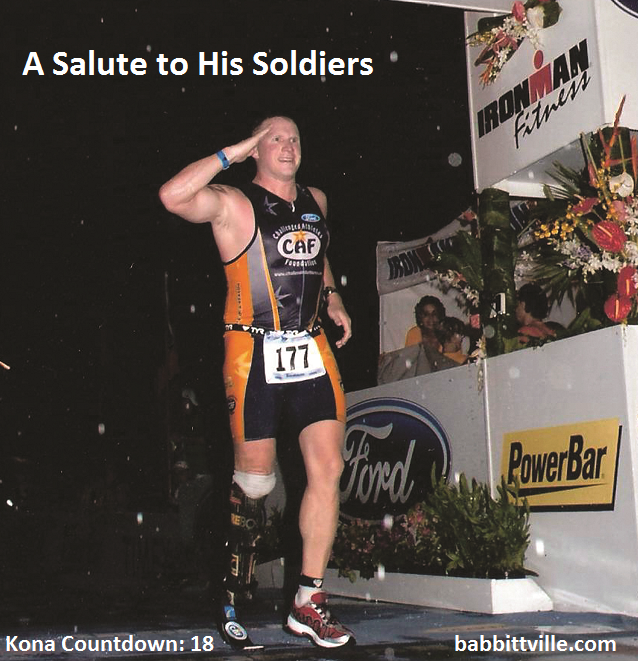

18

The date was June 21, 2003 and Captain David Rozelle was in his Humvee on a mission in Iraq. Their vehicle drove over an anti-tank land mine and Rozelle, who was sitting directly above where the explosion was centered, was bleeding profusely from his arms, legs and face. Within two hours Rozelle was at the hospital and the doctors were giving him two options. They could try and keep his lower right leg, but he’d have a club foot that would be useless. Or he could have his leg amputated and he’d be back running in a year.

“That was actually the option they gave me,” he laughs.

After the surgery, he ended up home in Fort Collins, Colorado and tried to adjust to life as a lower-leg amputee. “We’re human and sometimes we’re weak,” remembers Rozelle. When he wasn’t on morphine for the pain, he was self-medicating with whiskey. “I wasn’t being a good husband or a good father,” he continues. “I stayed up late, woke up late, and watched television all day. I couldn’t even drive.”

Then a letter arrived that changed everything. It was a letter he wrote to his wife, Kim, from Iraq before he was injured. At the time he wrote the letter, Kim was due to have their first child, Forrest, any day. “When I read the letter I realized the pain my wife would have felt if she received it after I had died,” he says.

Rozelle stopped using morphine, started training 3-5 hours a day, and completed his first triathlon. Eventually he passed his physical and was cleared to return to Iraq to resume his command.

In 2006 he went to Kona to attempt the Ironman World Championship. As he got to within a quarter mile of the finish. He stopped to towel off and to gather himself. “It was important to me to not only finish the Ironman, but to also look strong and powerful coming across the line,” he insists. “My soldiers needed to know that if I can do it, so can they.”

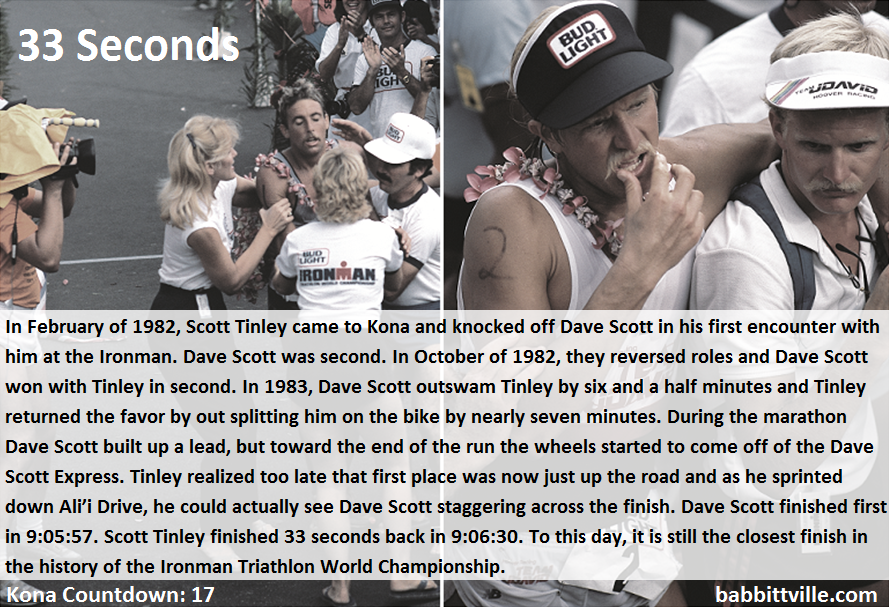

17

16

For Jon Blais, it all started in January of 2005 when he realized he was having problems at a party holding on to his beer. In February he crashed hard on his mountain bike and ended up with 15 staples in his head. “I never would have had such a stupid accident if I hadn’t started to lose control of my hands,” he said.

He went online and stayed up all night trying to figure out what was wrong with him. He realized that he had ALS, Lou Gehrig’s disease. He was officially diagnosed on May 2, 2005 at the age of 33.

When he was diagnosed with ALS, he was told that there was no treatment and no cure and that he had two to five years to live. As he treaded water in Kailua Bay for the 2005 Ironman, he had no idea if he could even finish the race because his body had deteriorated so rapidly.

He completed the swim in 1:50 rather than the 1:05 he would have swam before ALS. On race day he was forced to swim with only one arm. On the bike he couldn’t get out of the saddle and his calves and quads were seizing up throughout the ride. He made the bike cutoff time and headed out on the marathon to complete the race and become the first and only person with ALS to even attempt the toughest day in sport.

When the Voice of the Ironman, Mike Reilly, asked Blazeman before the race what his plans were for the finish line – maybe a Greg Welch style leap or a push-up, or ten – he responded by saying that he didn’t know if he’d be able to finish, but that Reilly might need to log roll his sorry butt across the line.

The Blazeman Roll has become a common site at the Ironman finish line by Ironman finishers everywhere and it’s a tribute to its creator.

Jon Blais passed away at the age of 35 on May 27, 2007, but the awareness he created that day and the charity he created to help find a cure for ALS will live on forever.

“You can choose to be pissed off or pissed on,” he told me in an interview after the race.

Blazeman, as always, chose the former.

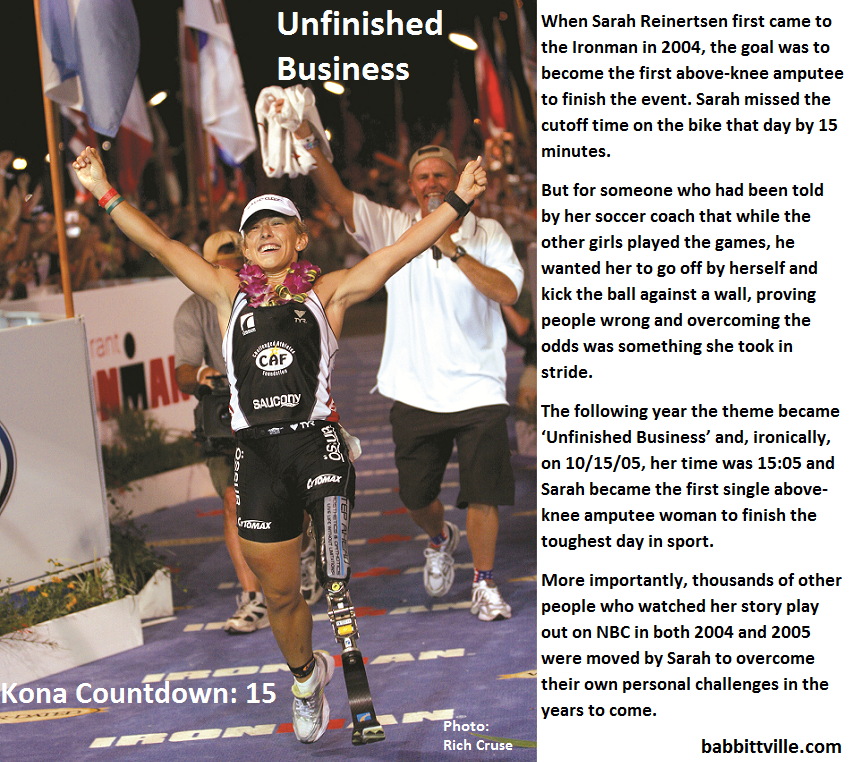

15

14

When Peter Reid of Canada won his first Ironman Triathlon World Championship title in 1998, it was a magical experience for him. But something felt different when he won his second title in 2000, beating his former training partner Tim DeBoom by a mere 2:09. “I won, but I wasn’t satisfied,” he recalls. “I crossed the line thinking ‘that was too close.’ I didn’t sit back and savor the win. The next day I was already planning my assault for 2001. That was the beginning of the end.”

He got back to training hard in November and never let up. By the summer his body started to fall apart. “I was so far into the overtraining syndrome that mentally, physically, emotionally and psychologically I was cooked,” he continues. “I was done. I needed to get away and I didn’t know if I was going to come back.”

He ended up dropping out of the 2001 Ironman and had basically retired from the sport. He spent his days in the summer of 2002 flying around on his motorcycle over his former bike routes.

He was in Starbucks one day with donut crumbs littering his leathers. A good friend named Rob Hasegawa approached him. He had watched Reid spiral downhill to the point where he couldn’t take it anymore. He placed an article by Mark Allen, ‘18 Weeks to Your First Ironman’ in front of Reid.

“Peter,” he said. “Go back to Hawaii and finish the damn thing. Then quit the sport with some closure.”

It was 15 weeks until race day so he was already three weeks behind. Reid lost 25 pounds over the next 15 weeks and the love of the sport came back. With a smile on his face, he ended up second to Tim DeBoom in 2002 and in 2003 he came back again and won his third Ironman World Championship title.

“In the beginning, I just loved to mix it up with the big boys,” he says. “Then I got to the point where I was scared to lose, where I was more worried about what my sponsors thought than following my passion.”

At the end of the day, winning that third title in 2003 was great. But, to me, Peter Reid’s second place in 2002 was way more important.

WATCH a Breakfast with Bob interview with Peter Reid here.

13

Dave Scott was the Roger Bannister of the Ironman. In his first win back in 1980 he took nearly two hours off of the existing course record. He was the first person to go under 10 hours, under 9:30, under 9:00, and under 8:30. He was also the first to run the marathon in Kona under 3:00 hours, under 2:55, and under 2:50. During his eight starts during the 1980’s, he won six times and finished second twice.

When he took second to Mark Allen in the 1989 Ironwar, ‘The Man’ went an astounding 8:10, took 18 minutes off of his existing course record, and ran 2:41 for the marathon.

Unfortunately injuries kept him off the starting line for five years, until 1994. At that point in time, Dave Scott was a 40-year-old dad. In the past he was racing Mark Allen and Scott Tinley. This time he was going head-to-head with someone who never loses, some guy named Father Time.

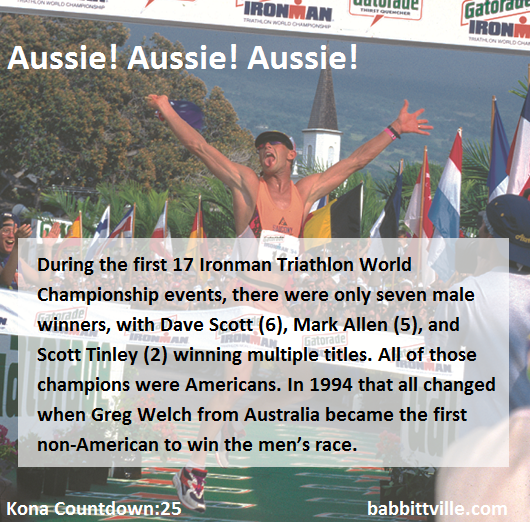

Early in the bike ride Dave Scott surprised everyone but himself by storming into the lead. Off the bike he kept Australia’s Greg Welch in sight and, heading into the Natural Energy Lab, he was only 11 seconds back. Welch was tougher that day and Dave Scott settled for his third second place finish, this time at the age of 40.

If you ask Dave Scott today to name his favorite Ironman race, there is a good chance that 1994, even though he didn’t win that day, just might be at the top of the charts.

Why?

Because his boys, Ryan and Drew, were there to watch daddy race the toughest day in sport, and because he proved to himself and everyone else that in Kona, at the Ironman, even if he’s 40 years old it’s a mistake to ever count Dave Scott out.

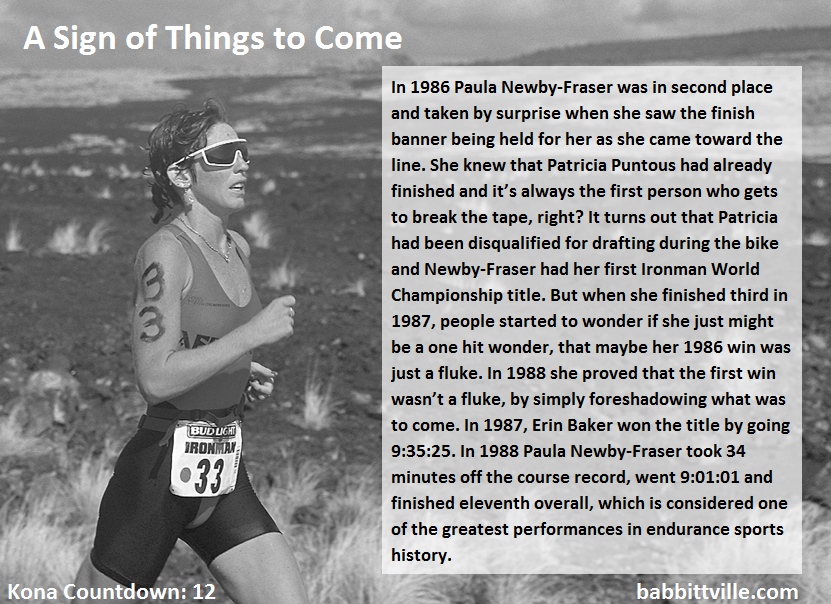

12

11

But when October rolled around, there they were and the race was full steam ahead. America’s Tim DeBoom had lost the year before to his former training partner, Canadian Peter Reid, by a mere 2:09. “I remember thinking at the finish,” remembers DeBoom. “I lost the Ironman by two lousy minutes. I knew that every time I went out for a ride, run, or swim during the next 12 months that two minutes would both haunt me and push me. Two minutes? You’ve got to be kidding!”

DeBoom was a man on a mission. As he ran through the final miles of the marathon in first place, fittingly the first American to win the Ironman since Mark Allen in 1995, the fans weren’t cheering ‘Go Tim!’ “They were cheering ‘Go USA, Go USA!’” says DeBoom. “It gave me goosebumps.”

10

Craig Alexander had immediate success on the Kona Coast. He took second in his first attempt in 2007 and then won in both 2008 and 2009. His game plan was simple: Stay within striking distance during the ride and then use his great running skills to win.

But going into the 2010 race, fellow Aussie and 2007 champion Chris McCormack came up with a plan of his own. “Craig is a front of the pack swimmer,” he insisted. “He is also the best runner in the heat in the sport. His one weakness is on the bike in the crosswinds out by Hawi. If everyone in the lead group works together to push the pace during that tough out and back section between Kawaihae, Hawi and then back to Kawaihae, we might be able to put some time on him. If we don’t, he’s going to win his third title in a row.”

It was obviously worth the risk. McCormack’s plan worked to perfection and Alexander was too far back off the bike to catch McCormack and ended up fourth, a little over six minutes back.

If you are a champion like Craig Alexander, you learn to adapt and change your game plan. In 2011, for the first time Alexander was wearing an aero helmet and was actually dictating the pace on the bike. His bike split in 2010 was 4:39:35. In 2011? 4:24:05, over 15 minutes faster than the year before. He had run an amazing 2:41:59 in 2010, but despite going so much faster on the bike in 2011, he only lost a few minutes off his marathon time and ran 2:44:03.

In 2011, Craig Alexander became the first man to win the Ironman 70.3 World Championship and Ironman World Championship in the same year, he went 8:03:56 to break Luc Van Lierde’s course record from 1996 by 12 seconds, and he joined an elite club with his third Ironman World Championship title.

9

Daniela Ryf of Switzerland had just won the Ironman 70.3 World Championship the month before the 2014 Ironman World Championship. As a multiple-time Olympian, under the tutelage of Coach Brett Sutton, she found that she had a natural talent to go long.

After a great swim and bike, Ryf was off on the marathon in first with Mary Beth Ellis, Jodie Swallow, Caroline Steffen and Rachel Joyce giving chase.

Mirinda Carfrae, the defending champion with two wins to her credit on the Big Island, was 14:30 back as she exited transition.

That’s a tough spot to be in as the defending champion and a lot of ground to make up. Sometimes your air conditioned condo sounds like a much better option.

“If you give in to that voice,” she says, “and quit and go home, how much pain is that going to put you in, knowing that you gave up, knowing that you gave in and knowing that you’re soft? That’s going to be much more pain than going through the pain of finishing the race. So I would prefer to be in agony and finish and say I did everything I could. I can go home and be happy with myself and look myself in the mirror. Or, if you give in to that voice, then it’s months of agony. It’s months of torture and torment knowing that you didn’t give it your all.”

Mirinda Carfrae did not quit and she obviously gave it her all.

Carfrae broke her own run course record that day, going 2:50:26, and passing Ryf for the win with about four miles to go. “I’m over the moon,” admitted Carfrae afterwards.

Who wouldn’t be? She won her third title, had the third fastest marathon of the day overall, broke her own run course record, overcame the biggest deficit in Ironman World Championship history, went 9:00:55 and edged out Ryf by a mere 2:02, 9:00:55 to 9:02:57.

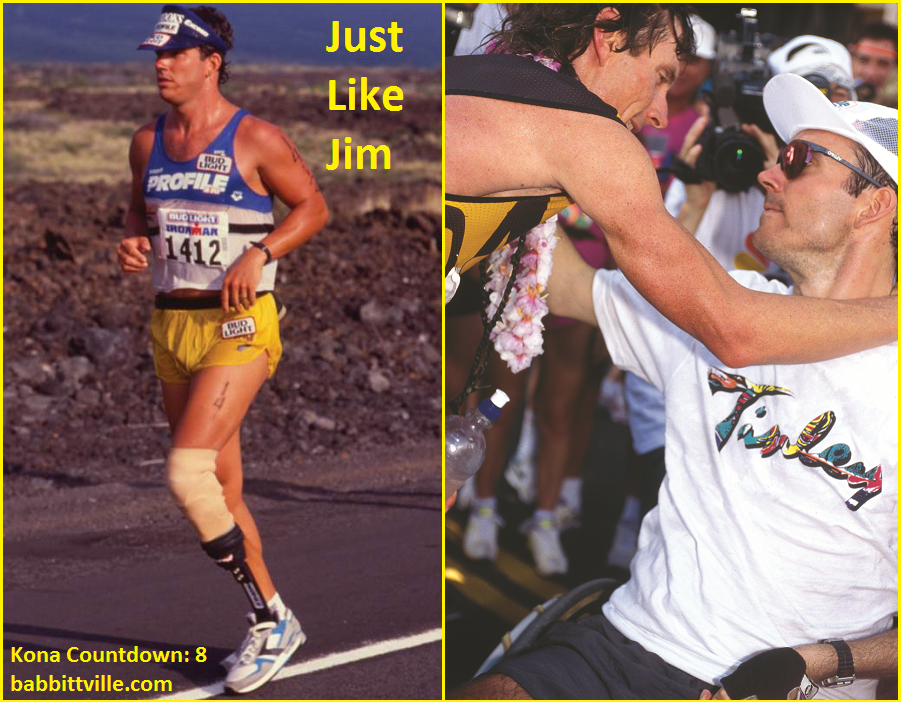

8

In 1985, Jim MacLaren was a 300-pound football player at Yale taking acting classes in New York City. He was going to class one day on his motorcycle when he was hit by a bus and thrown 90 feet in the air. He was declared dead on arrival, but lived and ended up having his left leg amputated below the knee.

MacLaren then set out to become the Babe Ruth of amputee athletes and, on a walking leg, ran a 3:16 marathon and went 10:42:50 in Kona in 1989. I covered Jimmy through Competitor Magazine as he was traveling the world as a sponsored athlete and watched him change the perceptions of what a challenged athlete could accomplish, especially in the lava fields of the Big Island.

In June of 1993, tragedy struck again. MacLaren was racing in Mission Viejo, California when a van went through a closed intersection, hit the back of his bike, and propelled him head first into a light post. He was now an amputee and a quadriplegic.

Through a group of friends, we were able to get Jimmy on a special flight that October to Kona so that the Ironman family could be there to support him.

Imagine becoming an amputee and coming back from that to reinvent yourself as an endurance athlete. Now imagine becoming a quadriplegic and wondering out loud if your new life was even worth the effort.

Jimmy was fragile and weak when he emerged from behind the curtain in his power chair to take center stage as his Ironman family stood as one to welcome him back to the Big Island of Hawaii.

Everything changed for Jimmy that night. I could see the glint in his eye return and knew our friend was back. The lava fields were the site of some of his biggest achievements and, from the reaction of the crowd, he knew deep in his soul that he was valued and he was loved. Jim MacLaren was the reason we created the Challenged Athletes Foundation and the impetus for CAF raising over $75,000,000 dollars in the past 23 years to keep challenged athletes in the game of life through sport. During that time frame over 13,000 grants have been sent out to help empower anyone with a disability to overcome the odds, push past limitations, never give up and see how far they can go.

Just like Jim.

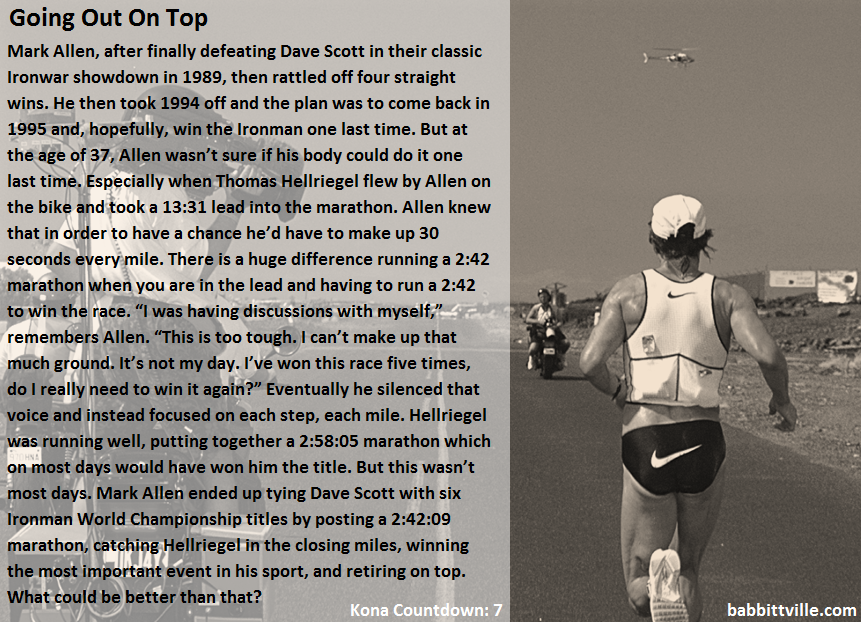

7

6

It was the toughest call she had ever had to make. Three-time Ironman defending champion, Chrissie Wellington, was forced drop out the morning of the 2010 race with a viral infection. Mirinda Carfrae went on to win her first Ironman World Championship title.

So when Wellington crashed hard during a group ride two weeks before the 2011 Ironman World Championship and ended up with contusions on her hip and shoulder plus extensive road rash from her thigh to her lower leg, she and her coach Dave Scott weren’t sure if she could even get to the starting line. Before the crash, Wellington knew she was in the best shape of her life heading into the 2011 race where she hoped to re-claim her title from Carfrae. In her mind, the last thing she wanted to do was not start the world’s most important triathlon for the second year in a row.

To compound the issue, doctors thought she might also have a torn pectoral muscle. A few days before the race, she had to have her wounds scrubbed out to avoid infection. While her training pointed toward a 53 or 54 minute swim, she came out of the water with a big smile on her face in 1:01. This would be her 13th Iron distance race and she was undefeated. But this time she was not only injured, she was going up against a woman who was the defending champion and was considered the best pure runner in the sport.

Her margin of victory in 2007 had been about five minutes. In 2008 it was 15 minutes and in 2009 it had ballooned to nearly 20 minutes. This was a woman who was used to dominating everywhere she raced and had ever been challenged.

This Ironday would be much different. Off the bike she was 22 minutes behind the leader, Julie Dibens, and ten minutes back of Rachel Joyce and Leanda Cave. Her time at the end was 8:55 and her margin of victory on Mirinda Carfrae was a mere 2:49, her closest race ever in Kona.

“Those were definitely my proudest racing hours,” Chrissie would say afterwards. “I was the last pro out of the water and came off the bike in sixth. I had to fight tooth and nail and I had never had to do that before. The fight is what I love, the fight is what I crave and the fight is what I got. Internally and externally I crossed that finish line physically and emotionally annihilated. I knew then that I was complete as an athlete.”

That turned out to be Chrissie Wellington’s last race.

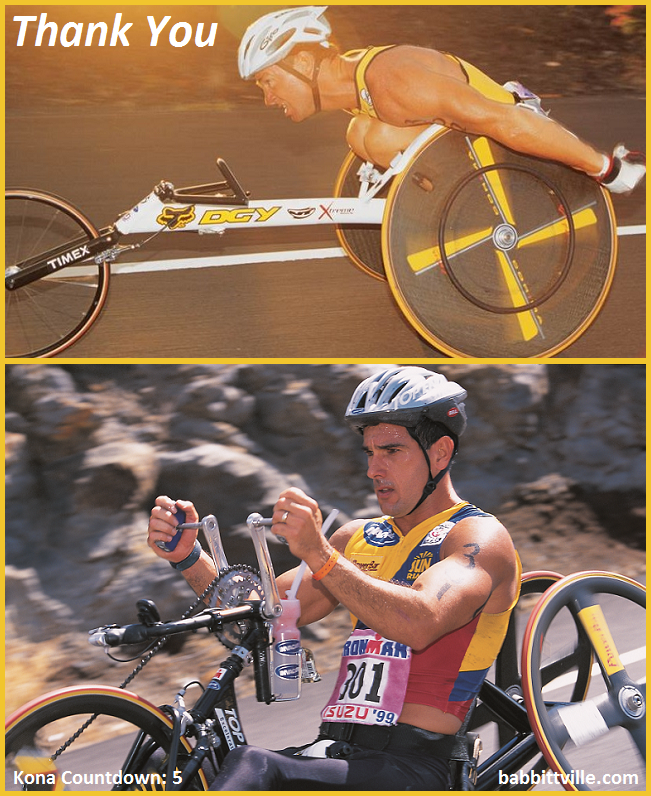

5

For three years, from 1998-2000, former Navy SEAL Carlos Moleda and motocross legend David Bailey went head-to-head in Kona in the handcycle division. Moleda had been paralyzed when he was shot in the back during a mission in Panama. Bailey was a legend in the sport of motocross and at the top of his game before he had been paralyzed during a training session.

For the first two years, Moleda had his way with Bailey. But heading into the 2000 race, Bailey looked fitter than he had ever been before. He knew that he had to put in ridiculous mileage in the pool, in his handcycle, and in his racing chair if he wanted to finally take down Moleda.

The two were on a collision course and it played out that way on race day. Moleda went by Bailey going up Palani early in the handcycle ride. Bailey caught him on the way back to town, but flatted with about six miles to go in the ride and Moleda got away.

Early in the marathon, Bailey was losing ground. But then all of those training sessions started to pay dividends and he caught and passed Moleda as they came out of the Natural Energy Lab.

When Bailey came across the line for the win, he waited for Moleda. When Moleda arrived, the two embraced and I could see Bailey whisper something to Moleda.

As we headed away from the finish, I asked Moleda what Bailey had said to him.

“He told me ‘Thank You,’” said Moleda.

“What?” I said in surprise.

“That’s what I said!” Moleda continued. “He said ‘thank you for pushing me to a level I never would have reached on my own.’”

The three year battle between the two of them was special because the word disability and the wheelchairs disappeared. What we had on race day was two amazing athletes who wanted nothing more than to kick the others guy’s ass.

How awesome is that?

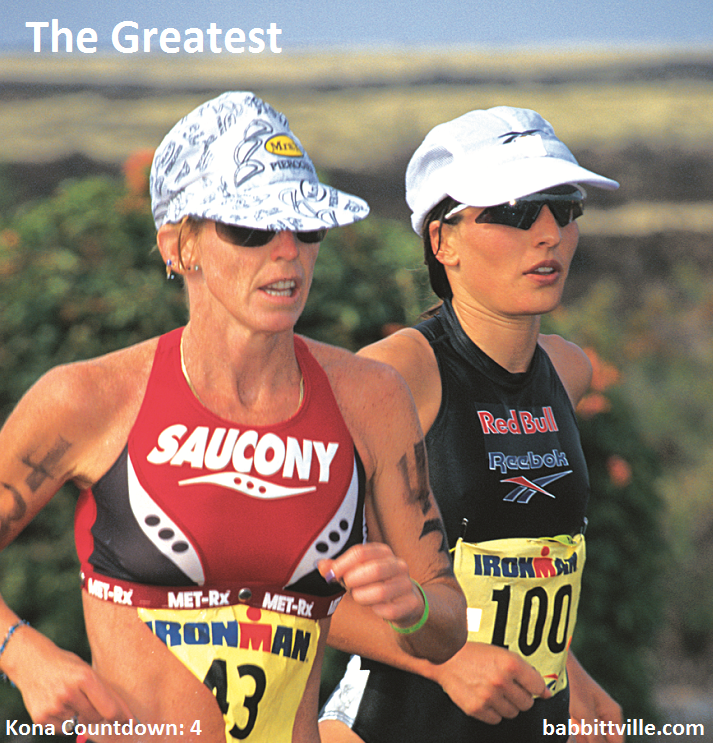

4

Paula Newby-Fraser had won in Kona seven times. The year was 1995 and, as usual, she built up a huge lead during the bike ride and looked to be on her way to win number eight. But something interesting happened on her way to the finish on Ali’i Drive. Newby-Fraser panicked during the marathon and stopped taking in nutrition. With about a half mile to go, the wheels came off the Newby-Fraser Express and Karen Smyers ran by her for the win, as Newby-Fraser staggered and then collapsed. After getting some fluids in, she walked to the finish in fourth place.

The most decorated Ironman in history showed that she was mortal.

So how do you come back from that? Easy. If you’re Paula Newby-Fraser you decide that you are tired of dominating the bike and going off the front. The bullseye was always on her back. Why not the other girls lead the race for a change? “I wanted to mix it up with the other girls,” she admitted.

During the latter part of the marathon, she was running with Iron Rookie Natascha Badmann. “I was enjoying myself,” said Newby-Fraser. “I knew that I was a good runner, so why not change things up a bit and try to win the race on the run rather than on the bike?”

And that’s what happened. Newby-Fraser ended up winning her eighth and final title by flipping the script and ditching her tried and true win the race from the front formula.

“To be honest,” she insisted afterwards. “I didn’t care if I won today or not. Which is probably why I did.”

3

As a dad, what would you do if doctors told you that your son Rick was a vegetable and that he should be institutionalized? If you’re Dick Hoyt, you ignore the experts and prove everyone wrong.

They started with Dick pushing Ricky at short running events but quickly moved up to the marathon. The Boston Marathon in the early years wanted nothing to do with Dick and Rick Hoyt. To qualify to get into their hometown marathon, 40-year-old Dick had to run under 2:50, a time that would qualify Rick, who was in his 20s. So they went to the Marine Corps Marathon and Dick pushed Rick to an unbelievable 2:45:23 and Boston was forced to let Dick and Rick into the event.

How things have changed! Now there is a statue on the Boston Marathon course of the ultimate father and his son.

When it came to the Ironman, Dick would need to pull Rick in an inflatable boat, ride with Rick in a specially built seat on the handlebars so Dick could keep Rick fed and hydrated throughout the ride, and then push Rick in a jogger during the marathon. In 1989 they completed the swim in 1:54:06, their bike ride was 8:01:30 even though the combined weight of Dick, Rick, and the bike was 376 pounds. Then Dick ran 4:30:27 for the marathon while pushing Rick, for a finishing time of 14:26:04.

What would a father do for his son? If you’re Dick Hoyt, that’s simple: Absolutely anything!

2

Throughout the 1980’s when there were only three television networks, every winter the Ironman World Championship would air on ABC’s Wide World of Sports. And every year from 1982 through 1989 the story line for the men’s race was exactly the same: Mark Allen, the world’s best triathlete 11 months of the year, was returning to Kona to go head-to-head with Dave Scott, the man who owned the Ironman.

They met for the first time in October of 1982. Allen’s derailleur fell off his bike as he was riding with Scott out by Hawi, and he had to DNF. In 1983, Scott won again and Allen took third. In 1984 Allen built an 11:30 lead on Scott by the end of the bike, fell apart in the run and took fifth, as Scott won again. In both 1986 and 1987 Allen took second to Scott. When Scott pulled out the night before the 1988 race, the stage was set for Allen to finally win the Ironman. He flatted twice and took fifth.

Which set up 1989. It was only right. If Allen was ever going to win the Ironman, he needed to knock off Dave Scott to do it. The day was epic. Allen wore yellow and Scott wore green. They stayed together all day long until Allen got away from Scott on the last uphill on the course. When the dust had cleared, Dave Scott had broken his own course record by 18 minutes and had gone 8:10:13. He ran 2:41:03, the fastest marathon ever up until that day. But Mark ran 2:40:04, which is to this day the fastest marathon ever run at the Ironman World Championship. Dave Scott summed up his day: “I don’t feel like I lost today,” said the six time champion. “I feel like I ran out of time.” The reality? On the best day Dave Scott ever had on the Big Island of Hawaii, Mark Allen was simply better.

READ MORE: Dave Scott and Mark Allen 1989 Ironwar

1

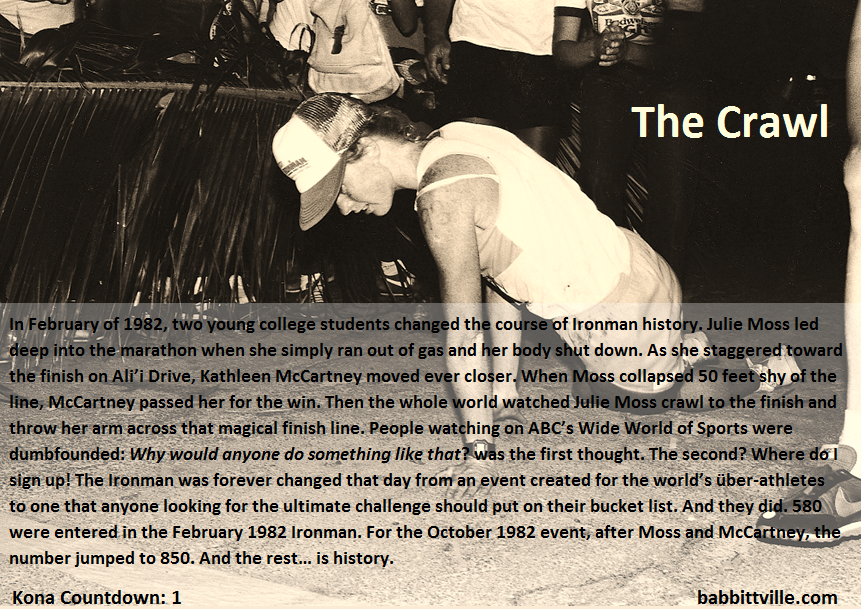

In February of 1982, two young college students changed the course of Ironman history. Julie Moss led deep into the marathon when she simply ran out of gas and her body shut down. As she staggered toward the finish on Ali’i Drive, Kathleen McCartney moved ever closer. When Moss collapsed 50 feet shy of the line, McCartney passed her for the win. Then the whole world watched Julie Moss crawl to the finish and throw her arm across that magical finish line. People watching on ABC’s Wide World of Sports were dumbfounded: Why would anyone do something like that? was the first thought. The second? Where do I sign up! The Ironman was forever changed that day from an event created for the world’s über-athletes to one that anyone looking for the ultimate challenge should put on their bucket list. And they did. 580 were entered in the February 1982 Ironman. For the October 1982 event, after Moss and McCartney, the number jumped to 850. And the rest… is history.

View Moments 50 – 26 here

24

24