Scott Brown and Chris Fuller fit the profile for Muddy Buddies perfectly. After all, the Muddy Buddy is for folks looking for a good time running and cycling with a little bit of pizzazz added to the equation in the form of mud pits, wall climbs and an inflatable or two to get over, around or through.

Brown was 33 at the time of the 2002 Muddy Buddy at MCAS Camp Pendleton north of San Diego, California. He grew up in Kauai, Hawaii and spent his early days surfing and mountain biking. Later he moved to Southern California and added the Muddy Buddy, trail running, and a few Adventure Races to his athletic résumé.

One day, he was working on his house and felt a little fatigued. “I told my wife, Marisa, that I was tired, that I needed a nap. She told me that I was getting old and to quit complaining,” recalls Brown. Not long after that, Brown was out surfing in Oceanside with Fuller. He knew this time that something was definitely not right. All of a sudden he was dizzy and his wetsuit felt tight, constricting. He caught a wave to shore. “I told Marisa what happened, and she told me to go see the doctor,” recalls Brown. “I never go to the doctor.” It’s nice he made an exception this time. The tests showed that he had an enlarged heart, which for an athlete is normal. But further tests showed that his heart’s ejection fraction was 12 percent. What does that mean in English? A normal heart is 50 percent; 35 percent is considered heart failure. Twelve percent? Make sure your papers are in order.

Thirty days later, the doctors installed an AICD (automated implantable cardioverter defibrillator) to help regulate his heart. Brown still exercised, but his heart was so weak that it was pointless. Plus, whenever his heart rate went over 240, he’d get zapped and wake up on the ground, not really remembering what happened. “My heart would just take off,” recalls Brown. “I would get what is called ventricular tachycardia, which means a rapid heard rate originating from the ventricles. The lower chamber of my heart would start going up to 240 beats per minute and the top chamber couldn’t keep up.” He could be lying in his bed watching television, and all of a sudden he would feel dizzy. He knew he was about to pass out. “I would pass out, get shocked and then wake up sweating,” says Brown. “Sometimes it would shock me before I passed out, which was really no fun. My life was saved so many times by the AICD.”

The doctors were monitoring him all the time. The prognosis? One third of the folks in his position get better, a third stay the same, and the other third get worse. In February 2004, Brown’s condition worsened drastically. His AICD went off at home. On the way to St. Joseph Hospital in Orange County it went off again. While he was at the hospital, it went off eight more times. The next day, while still in the hospital, he had to be cardio converted. You know, like you see on television: the guys and gals with the paddles shocking someone back to life when their heart can’t control itself. “My heart rhythm was not right, and they couldn’t get it back to normal,” says Brown. “Usually my AICD would go off and get it back to where it needed to be, but this time it didn’t work. So they drugged me to get me ready for the paddles. I was out cold, having a dream of some sort. But then I heard someone say ‘Are you ready?’ It was the doctors about to shock my heart back into rhythm. I thought they were talking to me, so I opened my eyes and said ‘ready for what?’ The last thing I remember them saying is ‘Wait, he’s not out . . . give him some more!’”

When his heart rate dropped back to normal, the doctors wanted to transfer him to UCLA; he needed major surgery. The insurance company said that he had to go to San Diego or the transplant would not be covered. Brown’s physician, Dr. Kelly Tucker, called the insurance company and told them that if he wasn’t transferred to UCLA immediately he would die. Brown was told that he had 24 hours to live and that his organs were shutting down. His options were simple: He needed a new heart or an artificial heart NOW. There is something called a heart list. Folks who are in the most desperate need are moved to the front of the line. One catch: There still needs to be a heart available for where you are on the list to even matter. The reality is that many have died while waiting for a heart that just never came. Brown was on the list for all of 30 minutes. Yep, 30 minutes. He was given 24 hours to live and within 30 minutes the doctors were notified of a 17-year-old heart that just became available.

“The coordinator told me she put me on the list, received an immediate response and got the chills,” recalls Brown. “She didn’t want to tell me until she ran it again just to make sure.” Another point of good karma: The transplant co-director was from Kauai and went to the same high school, Waimea High, that Brown did. “When he met me and found out that I was from Kauai, he left the room and said, ‘I’ll have to take care of the Kauai boy.’ That made me feel so much better,” says Brown.

The next morning, on February 10, Brown was the proud owner of a brand new heart. Five days later, he was out of the hospital. For the first three months he was at home, isolated from the rest of the world and all their colds and infections. “I was like the Bubble Boy character in Seinfeld,” Brown laughs. He saw his doctors every week for a month or so. Then it was every other week and then once a month. Brown laughs again. “They told me to stay out of the dirt.” Fat chance.

On August 15, 2004, Brown did just the opposite of staying out of the dirt – he crawled through the mud at the Muddy Buddy at Bonelli Park in Los Angeles with his best buddy Chris Fuller. Their name? Team Heart Throb. Just like in 2002, the two ran arm-and-arm to the finish line, coated with slop from head to toe. It had been a long time since they were able to share a feeling this good. For good measure, Brown actually carried Fuller across the line.

Over the next two years, Brown and Fuller completed two Muddy Buddy events in San Jose, California, one in Austin, Texas, and another one in Los Angeles. Plus, the two ran and walked the 2005 edition of The City of Los Angeles Marathon together in March with Brown running as a part of the Saucony 26 program, and, in February, he was honored as their Saucony 26 Man of the Year.

The following summer, the plan was for Brown and Fuller to go to Austin, Texas for the Muddy Buddy on Sunday, August 6, 2006. Brown and I were e-mailing back and forth the week before the event when he mentioned that he was having “a little bit of a valve issue.” I joked with him that a Ford has a little bit of a valve issue. When it’s in your transplanted heart, there is no such thing as a “little” valve issue.

When I returned from Austin on Monday, August 7, there was an e-mail waiting for me from Fuller. Scott Brown, his best friend in the world and the father of two little girls, had passed away over the weekend. The memorial for Scott Brown was held on August 10, which would have been his 38th birthday.

I’ll be honest. When my dad passed away in February 2006, at the age of 92, I was able to look at the funeral calmly as a celebration of a life well lived by a man well loved. For Brown’s special day, I was a soggy mess. He was too young and had too much left to live for. His girls would have to go on without their amazingly loving dad who told them every single day how much he loved them. My eyes well up now as I remember scanning the patio that day and seeing one photo of Brown with his hand on his chin, a sly smile on his lips, in his Saucony 26 pose.

Then there was another photo from Muddy Buddy with Fuller as they neared the finish. They both had their heads titled back screaming with everything they had to the heavens. Then I thought about all the lives he touched and how many people he inspired in that ridiculously short span of 30 months. When I first wrote about him, I called Scott Brown “Mr. Lucky.” Two and a half years later, I finally realize that the rest of us were the lucky ones.

[box style=”note”] In June of 1987, my business partner Lois Schwartz and I launched Competitor Magazine. We’re celebrating our 30th anniversary this month. I will be featuring a few of my favorite editorials and articles from the magazine. You can also check out 11 of my favorite covers here. [/box]

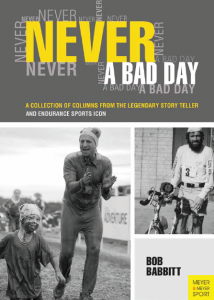

Mr. Lucky appears in my book: Never a Bad Day